Let's Close Read Another Poem

"my homies are always good / when i ask & i don't ask enough." - José Olivarez, "Ojalá: Me & My Guys"

Nazis unwelcome: here’s my post about moving this blog off of Substack soon. I might put this stinger on every post until then to try to irritate Nazi Sympathizer Hamish McKenzie. I might forget/get bored and stop. Not today though!

Cotton Xenomorph’s “Cryptids and Climate Change” issue continues, with “Angelus Novus” by Mileva Anastasiadou and two poems by Henry Kneiszel breathing fire on our literary Nostromo.

Now that you’ve read last week’s column and officially Like Poetry, let’s close read another poem, huh? What a must-click this newsletter is.

“Next week is gonna be epic,” I would say if this was 2010 or if I was a masterful gambiter. But that’s not a promise of anything exciting, I’m just gonna write about reading Homer next week.

The Odyssey rules, by the way.

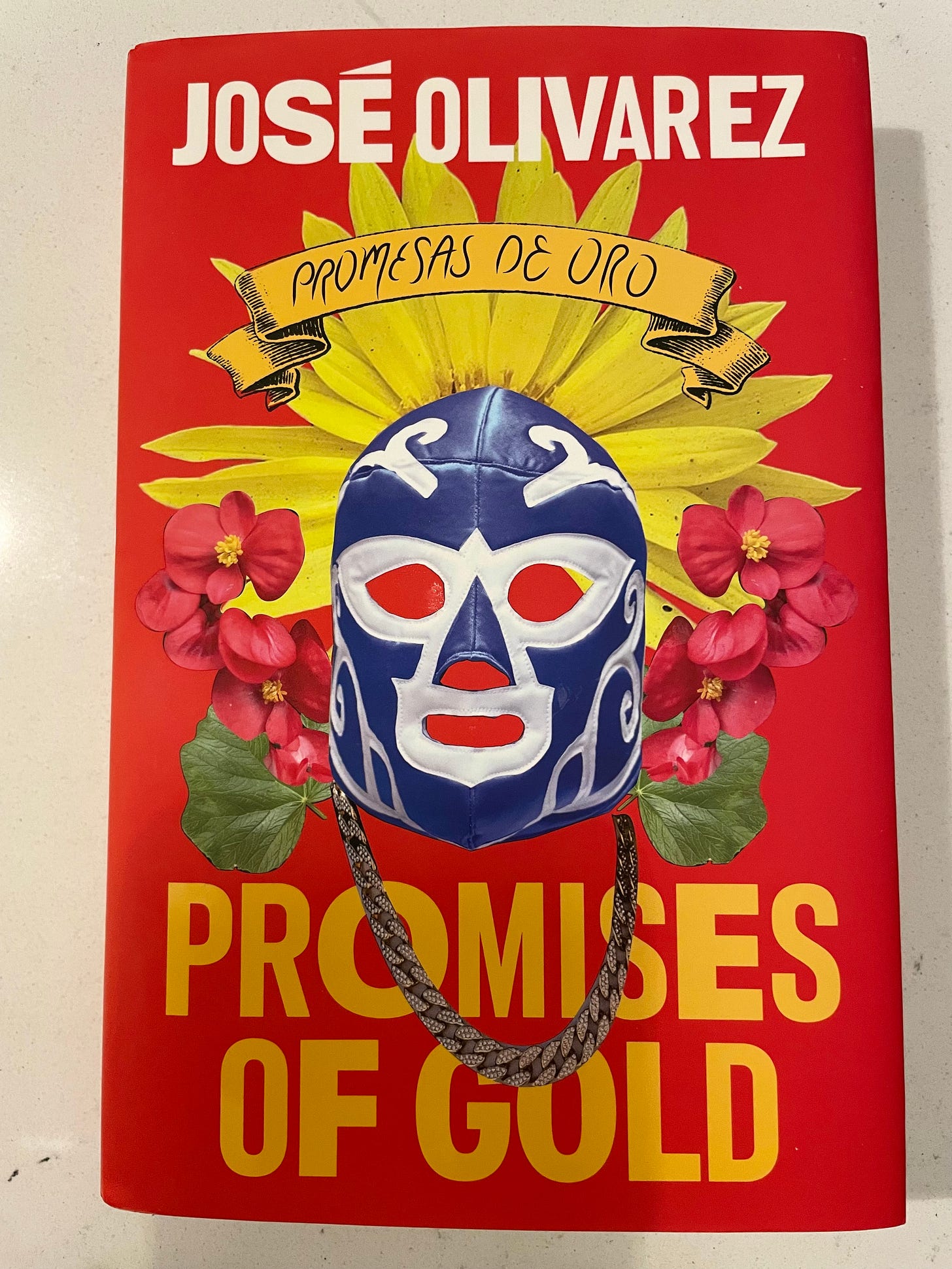

Last week, I close-read a poem I’ve been reading and thinking about for like 14 years. A poem that used to influence me a good bit, but now I simply enjoy. This week, I’m reading from one of my favorite poetry collections I read last year, something I said I’d re-read quickly but somehow a whole year has passed. We did have the author on The Line Break though. And this collection is definitely having an influence on my writing these days.

Like last week, here’s a photo of the poem, and then a typed version below instead of alt text. We’re reading “Loyalty” by José Olivarez.

“Loyalty”

i was loyal to my hair until it started receding.

i was loyal to chicago fitted hats.

i was loyal to chicago, but i still moved away.

i was loyal to chicago fitted hats until i shaved my head.

i was loyal to my baldness except when i was lazy.

i was loyal to my laziness especially during the pandemic.

it’s self-care, i said. i said, i’m being loyal to myself.

except my self-care started to look suspiciously

like self-neglect. the balding angel on my shoulder

said what’s the difference? sugar is loyal

to the heart. that’s what makes it dangerous.

Goddamn, I was flipping through the book (which I’m using to practice Spanish, there are translated versions of each poem, it’s so cool, buy this book) looking for a shorter poem, something I could type in the blog without taking too much space, and what a precision stab wound this poem is. You wanna know how precise this poem is? Notice the “especially - except - especially” trilogy in the middle of the poem. See how the rhythm of how similar those words sound lull you into forgetting the vastly different meanings those three clauses have? Oh man those poem rocks. Let’s talk music.

Music Image Metaphor

We’re going to talk about anaphora—the repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive clauses—at length in a bit, but I’ll say here that it’s a solid move to get out of “i was loyal to” after six lines. We’re obviously talking about music, but I’ve started to think of anaphoric stanzas as their own riffs in poems. It’s a good thing to have as part of the poem, but you don’t want Slash soloing during the whole song. Beyond anaphora, do yourself a favor and read this poem out loud as if you were talking to a coworker while you both are doing other things. Idk, I worked restaurants/retail, and this reminded me of like, opening or closing and telling my homie a story. Giggle and say “hey” before every line, that’s a fun reading.

The best image in this poem is chicago fitteds.

If you lived and were conscious from 2020 through when they announced vaccines for under-five-year-olds, I think you get the (main) metaphor. I’m not bald and yet this poem speaks to me. You’ve been through some sort of collapse before, some sort of breakdown. Had some sort of horrifying realization about the way you’ve been living. If you haven’t, then, wow, keep it to yourself.

The Line Breaks

How poets use line breaks is one of those things that used to have a lot of rules involving syllables and rhyme. Fortunately, English speakers/listeners/writers/readers came to their senses about all that bullshit. Anne Carson is right, the time between Homer and Gertrude Stein was a difficult interval for a poet. One might even say a boring interval for a poet, unless you were Persian or Japanese. Anyway, you can break lines whenever you want, so when a poet does so is interesting.

Line breaks are something that gets less cool the more you explain it, though. Like, I’m gonna point out the complete sentences and firm punctuation in the first seven lines. This declarative monotone gets disrupted, though. To be facile, it’s when the speaker1 starts to have this “self-care is becoming self-neglect” realization. That’s when things get less orderly, when the sentences start breaking at different points from the line. It’s when the speaker realizes all this orderliness in his life is actually disorder that the poem gets “messier.” What a juxtaposition! Genius stuff. Is life better when your lines break in the middle of sentences? Is controlled disorder the path to improvement? Is it simply naming the right demons? The poem’s not saying, but it’s making you wonder. Again, this is a facile reading for column inch purposes, but it’s a cool move.

A Quick Unscientific Note On Anaphora

Anaphora rules. It’s one of my favorite devices in the writer’s toolbox, and I’d use it in every poem/chapter of a novel if I could. I cannot, though, because a little bit goes a long way. Anaphora is good for building, anaphora is good for twisting meanings in interesting ways, anaphora is good for varying rhythm, anaphora is good for varying rhythm when you also throw in some other internal repetition, anaphora is good for varying rhythm when you’re reading live and you want to feel the audience move to the edge of their seat like oh shit the poet’s building to something, anaphora is good but yes, you can already picture how too much would get grating.

You know what anaphora is like? Harmonized guitar lines that are transitions or fadeouts. Polyphia does this in at the 1:24 mark of “Playing God,” between the main riff and the Animal Crossing section. Right here:

Brendan and I did this in “Curious” and “Hard Night’s Day” on our weight of an anchor album. Starting at 1:58 here:

If you’re writing a song, that’s a cheat code. Have one guitar player pick four notes, have the other harmonize it, play for like eight bars, buildup to the next thing. It’s always sick. But you can’t do it too much. Just like anaphora.

The Line Break Trilogy of Questions

Why this poem? like said, was looking for a shorter one, but it’s not like Promesas De Oro is hurting for short poems. Obviously, I’m hunting for a chance to discuss anaphora. Of course, you wanna pick a short poem that packs a punch if you’re gonna blog about it. For sure, José is really good at self-deprecation, which I’m really attracted to because I have a pretty low opinion of myself, but also is a hard thing to pull off without sounding cloyingly self-pitying. And yeah, I love a quick couple of stanzas that make you go “oof.” Man, you get into the “whys” and it’s mostly “because this poem rocks.”

What’s the move? What particular line or device resonates with you most? besides the anaphora, it’s the quick pivot to “…sugar is loyal / to the heart. that’s what makes it dangerous.” Build the whole poem out of those lines and it falls out of the sky. But that little head-shake of truth at the end there? Oh yeah, that’s the stuff.

What’s going on beyond the page? What does this poem do for you before and after you read it? Like I said before, I’ve been through my own slow breakdowns. Looking back on my life, there are several frog-in-a-pot situations I can look at—behaviors, relationships, habits, jobs, whatever. I didn’t mean to pick a poem that’d make me sentimental for this exercise, but seriously—I read this poem and think about how far I’ve come, who I owe for helping get out of various holes I’ve dug, and remind myself to stay on top of my shit. And someone else writing a poem that so closely fits into my own experience even though I must again stress that I have incredible shoulder-length wavy thick soft good-smelling yet dandruff-ridden hair—that’s the beauty of poetry, baby. You feel less alone.

Buy this book and all of José’s other books.

Sorry you got an email,

Chris

the speaker, who is not José, it must be said, because one of the most solemn shibboleths of poetry is that we always affirm the untruth “the speaker is not the poet” any time the speaker of the poem is mentioned.